EMERGENT SYSTEM BEHAVIOURS & GENERALIZABLE INSIGHTS

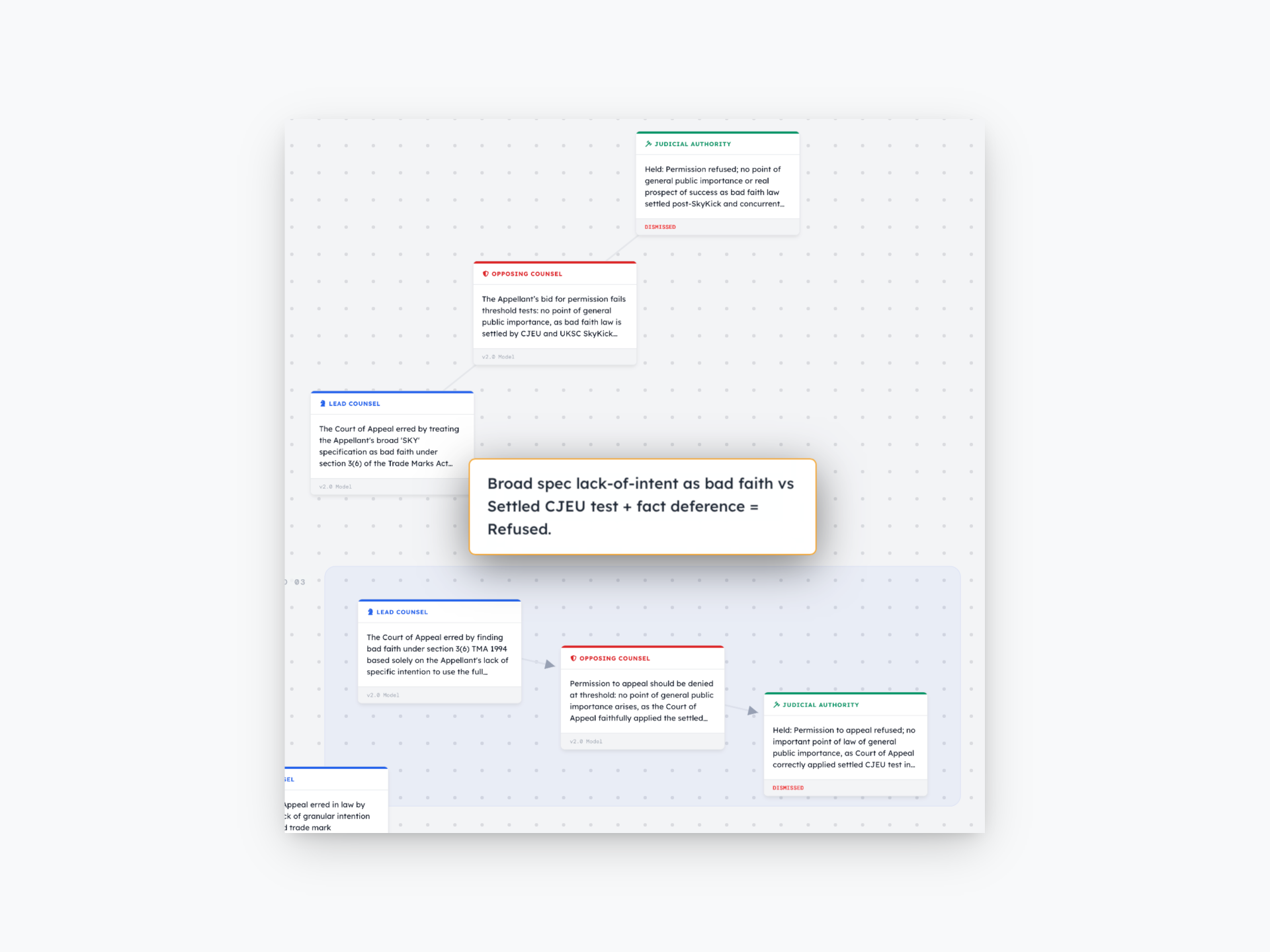

The nine test cases revealed not merely case outcomes but emergent behaviours, patterns arising from Lawgame’s adversarial architecture, judicial modelling, and multi-orbit recursion that were not designed into the system. They emerged from the play. These capabilities suggest the system develops something closer to strategic intuition rather than merely executing sophisticated search.

6.1 Strategic Failure as Information

Lawgame’s losses were often more strategically valuable than its wins. Unlike conventional litigation where failed motions are costs to minimise, Lawgame exploits them as data.

Case 2.1 illustrates this clearly. Across twelve adversarial rounds testing autonomy defences, jurisdictional challenges, and constitutional arguments, the system reached an honest conclusion in hours: the regulatory framework does not permit a winning defence on these facts. The dominant strategy is not to litigate. This analysis saved the client legal fees, reputational damage, and operational harm from pursuing an unwinnable fight. Knowing when not to fight is sophisticated strategic intelligence, demonstrated autonomously.

Case 3.1 reveals a different failure dynamic. Six rounds of lost fact-based defences systematically eliminated inferior strategies. In Round 7, the system pivoted to an entirely different register - arguing statutory coherence rather than factual merit. The six losses mapped judicial boundaries and made breakthrough possible.

Case 1.3 showed meta-learning. In Round 4, Lead Counsel generated an argument relying on evidence absent from the case corpus. The Judicial Authority agent flagged this gap; in Round 5, the system self-corrected, reformulating to use only evidence actually present. The adversarial architecture treats evidentiary gaps as vulnerabilities to be exploited.

The insight: strategic failure is information-rich. Lawgame’s capacity to extract learning from defeats - treating each as a data point narrowing the strategic search space - replicates a form of intelligence that pure prediction systems cannot.

6.2 Judicial Calibration

The Judicial Authority agent adapted more finely than anticipated, adjusting not just for broad jurisdictional tendencies but to specific case dynamics and procedural posture.

Case 1.1 (Chancery Division, England and Wales). The system identified that UK IP judges prioritise documentary evidence and statutory interpretation over testimonial inference. Lead Counsel deployed Git logs, clean-room protocols, and statutory analysis without attempting credibility narratives; effective in jury trials but poorly received in Chancery. This calibration emerged from judicial modelling, not explicit instruction.

Case 2.2 (Southern District of New York). Three failed rounds revealed the court’s receptivity to Supreme Court precedent and procedural rigour, not expansive constitutional claims. Round 4’s pivot to Escobar materiality was calibrated response to judicial feedback, not guesswork.

Case 3.3 (Texas Fifth District Court of Appeals). The system modelled the court’s preference for clean legal questions respecting jury findings. It filed a legal sufficiency motion - not a nuanced jury instruction challenge (which is notoriously difficult to challenge at the appellate level) - giving the court a doctrinally clean reversal path.

This consistency across three jurisdictions suggests genuine adaptation to institutional incentive structures, with practical implications: the same argument framed differently produces dramatically different outcomes.

6.3 Multi-Orbit Strategic Recursion

Orbit pivots often yield strategically superior outcomes, discovering Plan B that is dominant, not merely acceptable.

Case 1.2: The preliminary injunction objective failed repeatedly; courts were unwilling to grant extraordinary relief. But judicial feedback showed consistent receptivity to good-faith negotiation and early information exchange arguments. Orbit 2 pivoted to Rule 26(d)(1) expedited discovery - achieving the same strategic goal (forcing information revelation, shifting settlement equilibrium) through a mechanism the court would grant. Analysis suggests this was objectively superior: more durable on appeal, less vulnerable to modification, more directly addressing the information asymmetry.

Case 2.3: Direct assault on the Howey test seemed unlikely. The system pivoted to Rule 42(b) bifurcation, separating liability and damages phases to exclude prejudicial evidence. This fundamentally altered settlement calculus: with investor loss evidence excluded, the SEC’s expected trial value dropped substantially.

Case 3.1: Six rounds of fact-based arguments exhausted that register. Round 7 escalated to a qualitatively distinct argumentative category - statutory coherence - rather than incremental improvement. The pivot was exploratory: failures map judicial receptivity terrain, revealing paths invisible from the starting position.

6.4 Identification of Dominant Strategies

Two cases achieved optimal strategies requiring no pivots.

Case 3.2 achieved certiorari in one round: an unambiguous circuit split combined with an Erie doctrine jurisdictional defect created compelling Supreme Court intervention. The argument was so structurally sound the Opposing Counsel agent could not mount effective defence.

Case 3.3 achieved reversal of a $45 million verdict in one round. The legal sufficiency argument - expert testimony contained an analytical gap rendering it insufficient as a matter of law - was so cleanly framed the appellate court had unimpeachable basis for reversal.

These cases demonstrate strategic parsimony: knowing when the winning move is immediately available, deploying it without exhausting resources on alternative exploration. Human teams, uncertain and conditioned to expect resistance, frequently over-prepare. The system, unclouded by psychological dynamics, deployed the dominant strategy directly.

6.5 The Transparency Trap

Case 2.1 identified a generalizable structural vulnerability: public data can be used to deny disclosure of its analysis. Blockchain transactions are visible; the interpretive framework transforming raw transactions into evidence of wrongdoing remains opaque. The regulator controls the narrative while denying defendants tools to challenge interpretation.

Implications:

For blockchain/DeFi defendants: the regulatory deck is structurally stacked in enforcement based on public chain data. The defence cannot challenge what it cannot see.

For regulatory reform: mandatory disclosure of analytical methods may be required when enforcement rests on public data. If the state’s case depends on specific interpretation of open evidence, due process may require scrutiny of that interpretation.

For Lawgame: the Transparency Trap is incorporated as a recurring structural pattern for future testing.

6.6 The Materiality Trap

Case 2.2 revealed a generalizable pattern in False Claims Act enforcement: when a regulatory agency has actual knowledge yet continues reimbursement, licensing, or regulation, this creates powerful inference of immateriality under Escobar. The more successful the alleged fraud - measured by government payment volume - the less material, because continued payment despite known non-compliance evidences immateriality.

This means government administrative diligence becomes litigation liability. Thorough monitoring combined with continued business despite alleged violations undermines claims of materiality.

The pattern applies wherever regulatory administrative behaviour contradicts litigation posture:

- SEC enforcement where trading in allegedly fraudulent securities continued

- FDA enforcement where labelling or manufacturing approvals continued for allegedly misbranded drugs

- FCA enforcement where the regulator continued supervising firms allegedly operating in breach

In each, the question is identical: if the violation was material, why continue payment/approval/authorisation? The regulator’s own conduct undermines its materiality claim.

This generalizable insight applies to future government enforcement cases: systematically explore whether the Materiality Trap is available.

6.7 Procedural Leverage as Superior to Substantive Victory

Across multiple cases, procedural victories proved more strategically valuable than substantive ones; a game-theoretic dynamic well understood but underutilised in practice.

Settlement decision is driven by expected value: win probability × damages × litigation costs discount. Procedural manoeuvres altering these variables shift settlement equilibrium without requiring substantive victory.

Case 1.2: Expedited discovery was more valuable than preliminary injunction would have been. The injunction would face immediate appeal and potential stay. Discovery forced irreversible information shift - once revealed, documents cannot be un-revealed - creating settlement pressure the vulnerable injunction could not match.

Case 2.3: Bifurcation did not resolve securities offering question. It removed emotionally charged investor loss evidence from the liability phase, separating liability from harm and reducing case value to prosecution.

Case 3.3: Legal sufficiency motion guaranteed reversal if the standard was met. Jury instructions appeals result in remand with continued exposure; legal sufficiency achieved outright reversal and final judgment.

The principle: when facts are unfavourable, the most productive strategic investment is often not arguing facts more persuasively but changing the procedural frame within which they are evaluated. Lawgame systematically explores procedural alternatives alongside substantive ones, identifying these opportunities with consistency time-constrained human teams cannot match.