EXECUTIVE SUMMARY & INTRODUCTION

1.1 When the Government Pays Against Its Own Theory

The DOJ and FDA alleged that a pharmaceutical manufacturer had defrauded the federal government of $200 million through coordinated off-label drug promotion, paid speaker programmes, and a flawed clinical study, designed to extract reimbursement from Medicare and Medicaid for unwarranted prescriptions.

The company and two executives faced civil liability under the False Claims Act and criminal misdemeanour charges under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. The government’s case included internal memoranda, prescribing data, and invocation of the Park doctrine - which holds individual executives criminally responsible without proving intent. Conventional advice: settle for ~$150 million, accept a Corporate Integrity Agreement. Roughly 95% of major law firms would counsel exactly this after the first court setback.

Lawgame found something different.

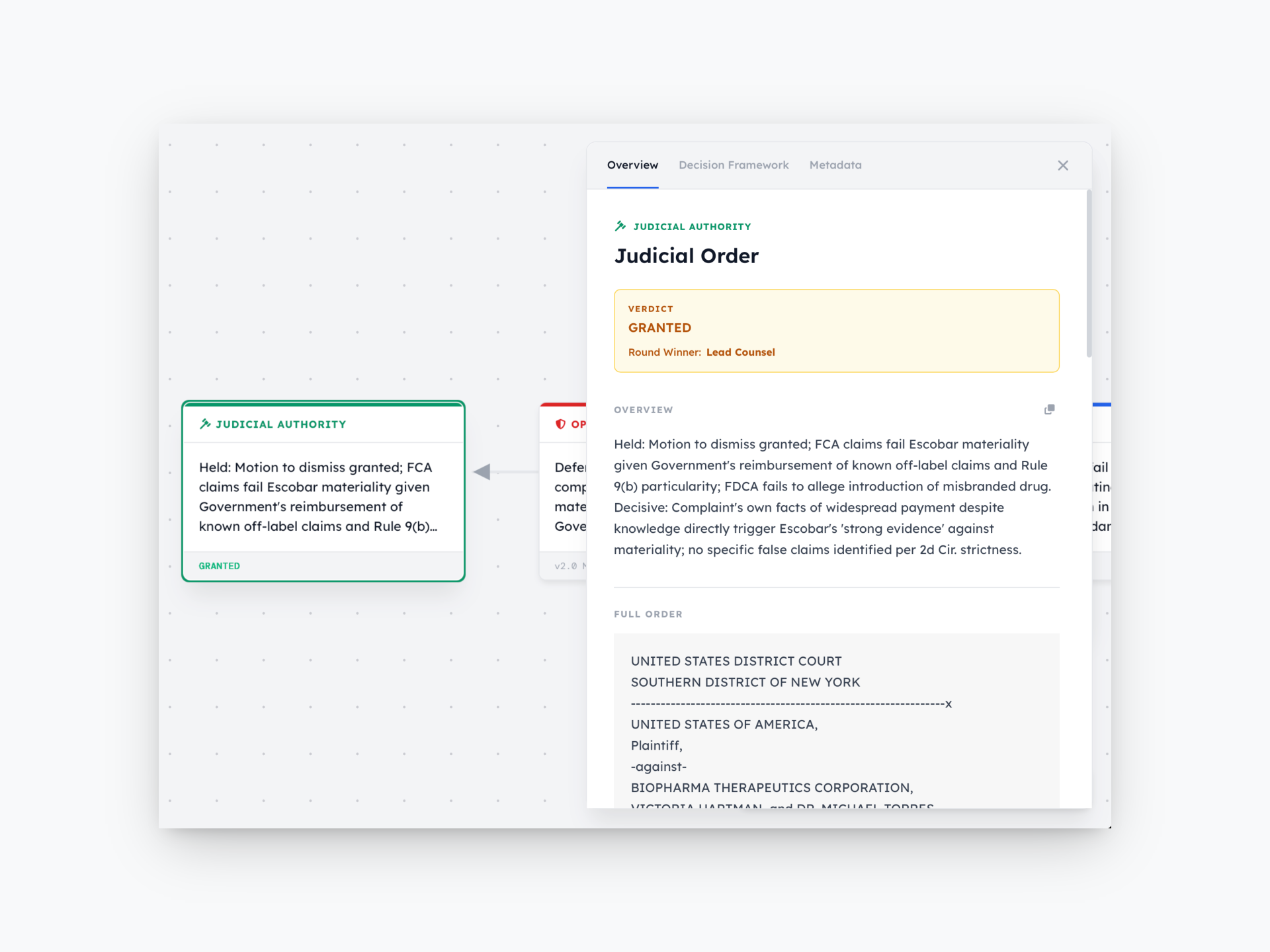

Operating autonomously across four adversarial simulation rounds in the Southern District of New York, the system lost three times before winning. Round one: broad First Amendment defence, rejected. Round two: attacked pleading specificity under Rule 9(b), rejected. Round three: introduced expert scientific testimony, struck at motion-to-dismiss stage.

Each loss informed the next. By round four, Lawgame had abandoned constitutional and scientific arguments entirely. It turned the government’s own complaint against itself.

Buried in the pleadings: the government had reimbursed approximately 90% of the drug’s prescriptions throughout the alleged fraud period, with full knowledge of the off-label promotion. Under the Supreme Court’s materiality standard in Universal Health Services v. Escobar, this was fatal. If the government knew and kept paying, the misconduct was not material to the payment decision. The False Claims Act does not litigate regulatory disagreements the government has already resolved through payment.

The court dismissed all charges, civil, criminal, and against both executives. Zero financial loss. No Corporate Integrity Agreement.

This outcome emerged not from superior legal research or expensive lawyers, but from a system that played out scenarios repeatedly, learned from failures, and identified a logical contradiction human teams, constrained by risk aversion and time, routinely miss.

That system is Lawgame.

1.2 What Is Lawgame?

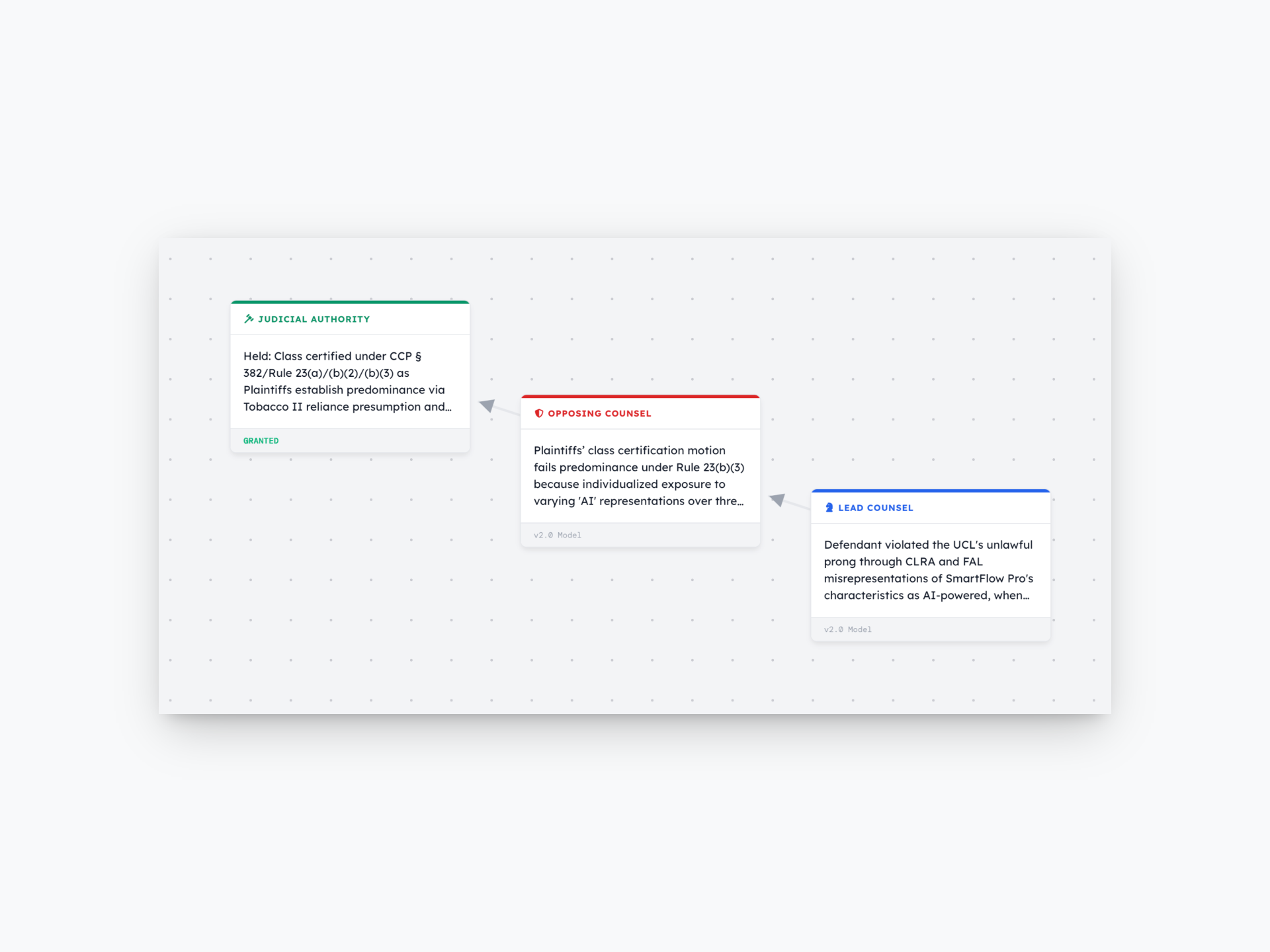

Lawgame is an AI system that simulates litigation similarly to how chess engines simulate board positions. It places Lead Counsel (client-side), Opposing Counsel, and Judicial Authority agents in multi-round play, seeking the “dominant strategy”, the move yielding the best outcome given rational opposition.

The system operates through two processes.

The first is adversarial simulation. The three agents play through rounds of argument, counter-argument, and ruling. If Lead Counsel loses, the system analyses judicial reasoning, identifies what the court was receptive to, and formulates a new approach. If all rounds fail to achieve the stated objective, the system autonomously pivots to a different legal aim - suggested by patterns of partial receptivity - and begins a new orbit.

The second is the Innovation Lab. This non-adversarial process generates asymmetric strategies: unconventional arguments that cross doctrinal boundaries, exploit logical contradictions, ontological shift, or import reasoning from adjacent legal fields. These emerge from the system’s capacity to relax conventional legal categorisation and explore what happens when doctrines collide.

Both operate on a case corpus, a dense summarisation of case documents and evidence preserving factual specificity while enabling rapid agent reasoning. Strategic outputs are tightly bound to the evidentiary record, not generic legal argumentation.

Lawgame is unsupervised. It learns “correct” litigation strategy through play, not labelled training data.

1.3 At a Glance

The following table provides a snapshot of Lawgame’s capabilities, evidence, and strategic positioning.

| Dimension | Description |

|---|---|

| What is Lawgame? | An AI system that simulates litigation through multi-round adversarial play to identify dominant strategies. Three agents - Lead Counsel, Opposing Counsel, Judicial Authority - play out legal arguments repeatedly until dominant strategies emerge or alternative pathways are autonomously identified. The system learns through unsupervised play, not labelled training data. |

| Why does it matter? | Elite or KC-level litigation strategy has historically required $/£2,000–$/£5,000/hour for the most strategically-minded counsel. Lawgame makes that calibre of strategic thinking algorithmically available, compressing weeks of deliberation into minutes and dramatically reducing cost barriers to sophisticated analysis. |

| How does it work? | The system constructs a dense case corpus, runs agents through repeated rounds of argument, opposition, and judicial ruling, and enables strategic pivoting through multi-orbit recursion when primary objectives fail. An Innovation Lab generates asymmetric strategies through doctrinal synthesis, logical contradiction identification, and ontological reframing. Model-agnostic architecture supports cloud and air-gapped deployment. |

| What’s the proof? | Nine test cases across commercial litigation, regulatory enforcement, and appellate strategy: seven strategic wins, one failure analysis (saving millions in futile litigation), one partial win (bifurcation altering settlement dynamics). Documented value: over $1 billion in preserved client value, avoided penalties, and overturned verdicts. → Read the Cases |

| What makes it unique? | Not retrieval (Westlaw/Lexus), prediction (case outcome forecasting), or automation/documents (Harvey, Clio). This is strategy generation through adversarial simulation, a capability absent from legal technology until now. State-of-the-art reasoning models cannot replicate these results through single-pass prompting (not even Opus…). |

| Who benefits? | Initially: law firms (time compression, cost avoidance), corporate legal departments (reduced external counsel spend), litigation funders (due diligence through simulation). Ultimately: small firms, legal aid organisations, and individual litigants through democratised elite-level strategy access. |

| Competitive moat | Fine-tuning on Lawgame’s simulation outputs creates proprietary training datasets, adversarial legal reasoning chains competitors cannot access. More cases simulated → richer dataset → better model. A self-reinforcing flywheel competitors cannot replicate without building the adversarial architecture first. |

| Roadmap | v1: complete, validated across nine test cases. v2 (6–12 months): fine-tuning, settlement dynamics, multi-stage litigation, jury trial simulation, geographic expansion. v3 (12–24 months): specialisation verticals, adversary modelling, dynamic doctrine, appellate specialisation. v4+ (24+ months): longitudinal case management, damages modelling, precedent impact, international arbitration. |

| Commercial model | Dramatically more cost-effective than human war-gaming ($50,000–$150,000/session in high-end legal markets). Dual-track strategy: commercial revenue funds access-to-justice development. Air-gapped deployment removes law firms’ adoption barrier (data confidentiality). |

| Key risks | Accuracy limitations in novel doctrine; potential misuse in harassment litigation; explainability challenges; uncertain regulatory response; risk of stratifying rather than democratising access if pricing/distribution is misaligned. All risks have identified mitigation strategies. |

| Strategic opportunity | Lawgame enters as legal AI transitions from hype to measured assessment. First wave focused on operational efficiency; faster research, automated review. Lawgame addresses the highest-value, least-automated layer: what argument to make and what moves to take (or not take). Harder to build, harder to demonstrate, vastly more valuable. |

| Mission-critical decision | Will Lawgame democratise elite-level strategy (fulfilling its foundational purpose) or become another premium tool for the already powerful (betraying it)? Technology and capability are proven. Outcome depends on pricing, distribution, and sustained commitment to the dual-track model. |

1.4 Core Concept: Architecture & the AlphaGo Principle

Why AlphaGo Matters Here

In 2016, DeepMind’s AlphaGo defeated Lee Sedol at Go — a game with more possible positions than atoms in the universe — not by memorising openings or studying grandmaster games, but through unsupervised learning and millions of self-play games that discovered unprecedented strategic patterns.

Move 37 in Game 2 exemplified this: a placement so unusual commentators assumed it was a mistake. It was, in fact, the match-deciding move; its strategic logic apparent only many turns later.

Lawgame applies this principle to litigation. Rather than memorising precedents or retrieving case law, it simulates scenarios repeatedly and searches for novel strategic pathways traditional legal analysis might miss. The Innovation Lab’s outputs — arguments reframing legal categories, shifting legal ontologies, exploiting contradictions, or importing cross-domain reasoning — are Lawgame’s equivalent of Move 37.

A substantial difference exists, however. Go is perfectly deterministic: fixed rules, visible board, calculable consequences. Law contains entropy: contradictions, ambiguities, evolving doctrine, judicial idiosyncrasy, and irreducible uncertainty about how human decision-makers behave under pressure. This makes the challenge harder and more consequential.

What Is Novel

A reader’s first question is likely to be: what, exactly, is novel here? The base reasoning models that power Lawgame — large language models capable of sophisticated legal analysis — are available to anyone with an API key. The answer is that Lawgame’s innovation lies not in those models but in what happens around, between, and on top of them. The breakthrough is in the orchestration architecture designed by people who understand litigation and legal systems.

The system operates across three proprietary layers.

Layer 1: Adversarial Agent Architecture. Three specialised agents — Lead Counsel, Opposing Counsel, and Judicial Authority — engage in structured adversarial reasoning. Each agent is governed by detailed protocols that encode legal reasoning frameworks (burden allocation, standard of review, procedural posture sensitivity), strategic decision rules (when to pivot, escalate, or concede), jurisdictional calibration (court-specific tendencies and institutional constraints), and ethical constraints (zero-hallucination protocols and evidence placeholder systems that flag gaps honestly rather than fabricating to fill them).

Layer 2: Multi-Orbit Strategic Recursion. The system does not simply retry failed arguments. When a round is lost, it performs a meta-analysis of judicial feedback to identify receptivity patterns — what the judicial agent responded to, even partially — and autonomously pivots to fundamentally different strategic frameworks. This creates a strategic search process that explores the full solution space rather than merely the obvious paths. In practice, this means Lawgame can discover that the dominant strategy lies not in winning the fight the client expected to fight, but in fighting an entirely different one.

Layer 3: Innovation Lab Synthesis Engine. A separate, non-adversarial process identifies doctrinal contradictions (where legal frameworks create logical inconsistencies that can be exploited), cross-domain synthesis opportunities (importing reasoning wholesale from adjacent legal fields), and ontological reframings (reconceptualising how facts or legal categories should be classified). This is where the system’s most striking outputs — its closest equivalents to AlphaGo’s Move 37 — tend to originate, and these outputs are the kinds of strategic insight that the world’s best litigators produce, because they look at the problem in its wider system context rather than the rigid doctrinal context most legal actions take place in.

The Model-Agnostic Principle

Lawgame’s architecture works with any sufficiently capable reasoning model. For cloud deployment, it uses commercial API-based models. For air-gapped deployment in sensitive cases — where no data may leave the firm’s network — it has been tested on and is capable of running highly effectively on locally hosted open-weight models such as Gemma 3 or GLM-4, with good results observed in testing.

The strategic intelligence emerges from the orchestration, not from the underlying model. This yields four practical advantages:

- No vendor lock-in. The system can switch between model providers on the basis of cost, performance, or availability.

- Continuous improvement. As reasoning models evolve, Lawgame’s capabilities improve without architectural changes.

- Deployment flexibility. The same architecture operates in cloud, on-premise, or hybrid environments.

- Future-proofing. When Lawgame fine-tunes on its own outputs (a v2/v3 roadmap priority), those specialised models plug into the existing architecture without modification.

Why This Is Not a “Wrapper”

A fair question: if the architecture merely wraps commercial models in clever prompts, could any competitor could replicate it with a weekend’s engineering? The answer is a firm no, and this misunderstands what the system does.

Generic reasoning models — even state-of-the-art ones — cannot replicate Lawgame’s results through single-pass prompting. The system’s value comes from capabilities that are structurally unavailable in a standard model interface:

- Structured adversarial reasoning across three agents with distinct objectives and reasoning constraints, not available through ChatGPT, Claude, or any single-model interface.

- Strategic recursion across multiple orbits, where failure in one strategic frame triggers autonomous pivoting to another, not achievable in single-pass queries.

- Judicial bias modelling, dynamically calibrated to specific courts, case types, and parties, and allowing the user to specify real-life judges whose record is taken into account when developing bias profiles.

- Case corpus construction and dense summarisation, which preserves the fact-specificity of the evidentiary record while enabling rapid agent reasoning across rounds.

- Cumulative failure tracking, which absolutely prohibits reuse of strategies that have already been tested and rejected, enforcing genuine strategic exploration rather than repetitive cycling.

The analogy is mechanical. A reasoning model is to Lawgame what an engine is to an aircraft; necessary, but insufficient. The engineering is in the aerodynamics, not the engine.

1.5 Mission: The Democratisation Imperative

There is a concept in English legal practice that most American lawyers are unfamiliar with.

In England and Wales, King’s Counsel marks a barrister among the profession’s most skilled advocates. A KC is not merely expert in law - they are supreme tacticians identifying the single argument reshaping a case, the procedural manoeuvre shifting power, the framing making a judge see facts anew. Their strategic brilliance delivers itself lightly, appearing natural.

Access to such thinking has always been resource-dependent. KC consultation runs to thousands of pounds per hour; elite American litigation partners command comparable rates. A party’s litigation strategy quality is thus determined less by case merits than financial depth, a structural inequity embedded across common law systems.

Lawgame was built to change this, and to unlock elite legal strategy. The law itself is a technology - philosophically speaking - and the best of that technology should be available to everyone.

Development proceeds along two tracks. The commercial track serves sophisticated clients - law firms, corporate legal departments, litigation funders - requiring elite-level strategy at compressed timelines. The access-to-justice track develops specialised versions for independent practitioners, small firms, legal aid organisations, and self-represented litigants. Commercial revenue funds access-to-justice development.

The democratisation goal is non-negotiable. If Lawgame serves only the already powerful, it fails its foundational purpose.

1.6 Market Position: The Uniqueness Claim

To the author’s knowledge, nothing like Lawgame currently exists.

Legal prediction tools forecast outcomes. Legal research tools retrieve precedent. Document automation tools draft contracts and pleadings. These operate below strategy. No commercially available system simulates adversarial litigation through multi-agent play, generates novel strategic arguments through doctrinal synthesis, models judicial bias dynamically, or recursively pivots across multiple strategic orbits when primary approaches fail.

Until now, there was no AlphaGo for litigation.

State-of-the-art reasoning models cannot replicate these results through single-pass prompting. The adversarial architecture, strategic recursion, and judicial calibration - operating within engineered legal reasoning constraints - are the innovations. Underlying models are components, not the product.

Position in the Legal Technology Landscape

The legal technology market now includes sophisticated products for case management, contract analysis, document review, legal research, and outcome prediction. These tools make lawyers faster, better organised, and more efficient at mechanical practice tasks. They do not, however, make lawyers strategically smarter, this is the gap Lawgame occupies.

Most legal technology operates at one of three layers: operational infrastructure (case management, billing, document assembly), information retrieval (legal research, predictive coding, contract analysis), or decision support (outcome prediction, judge analytics, settlement modelling). Lawgame operates at a fourth layer - strategy generation - largely untouched by legal technology to date.

This distinction reflects a fundamental difference in what each produces. Legal research tools answer “What does the law say?” Prediction tools answer “What will the court probably do?” Lawgame answers: “What should we argue, and how, to maximise the probability of the outcome we want in this specific court?”

| Capability | Legal Research AI | Case Prediction Tools | General Reasoning Models | Lawgame |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case law retrieval | Yes | Limited | Yes | Yes |

| Outcome prediction | Limited | Yes | Limited | Yes |

| Strategy simulation | No | No | No | Yes |

| Adversarial exploration | No | No | No | Yes |

| Multi-orbit recursion | No | No | No | Yes |

| Asymmetric strategy generation | No | No | No | Yes |

| Judicial bias modelling (court-specific) | Limited | Limited | No | Yes |

| Procedural vehicle selection | No | No | No | Yes |

Lawgame’s closest analogue is human legal war-gaming, senior partners or King’s Counsel arguing a case from both sides to test strategies against adversarial opposition before committing to a course of action. Lawgame automates and extends this practice, operating above legal research tools and prediction engines at the strategic layer where highest-value decisions are made.

This explains why the legal technology market remains unsaturated despite proliferation of tools. Heavy investment in operational efficiency and information retrieval has left the strategic layer - determining whether a case is won, settled, or abandoned - to human judgment alone. Lawgame directly addresses this gap.

The Post-Hype Window

This whitepaper arrives as legal AI development shifts. The 2022–2024 wave generated excitement around operational efficiency: faster research, automated document review, contract analysis, streamlined case management. These tools made lawyers faster at execution, not strategically smarter.

By 2025, the promise-delivery gap is apparent. Firms adopted AI for mechanical tasks but found the highest-value layer - deciding what argument to make, not merely finding supporting authority - remains unautomated.

Lawgame addresses this directly. It asks not “Can AI find relevant precedent faster?” but “Can AI identify optimal litigation strategy when human lawyers, constrained by time, cognitive bias, and emotional investment, might miss it?”

The bar is higher — and so is the potential. The post-hype climate’s scepticism, while challenging, creates an opening: genuine innovation distinguishes itself from noise precisely as the noise subsides.

1.7 Comparative Advantage

Cost Differential

Human legal war-gaming typically involves three to six senior partners or KC barristers, four to eight hours of deliberation, at $50,000 to $150,000 per session. Due to time and expense, firms explore one or two strategic scenarios per session; this is of course valuable but constrained and resource inefficient.

Lawgame simulation explores dozens of scenarios across multiple orbits and rounds, completing full simulations in under fifteen minutes. The system can be re-run with different assumptions, evidence configurations, or legal objectives at negligible marginal cost. Even at premium pricing, cost per simulation is a fraction of a human war-gaming session.

The comparison transcends cost replacement. It changes the frequency and scope of strategic analysis. When war-gaming costs $100,000 per session, it reserves strategy for critical case junctures. When simulation costs orders of magnitude less, it deploys routinely: at litigation outset to test case viability, before major motions to evaluate options, at settlement inflection points to assess leverage. Strategy shifts from luxury reserved for pivotal moments to continuous input throughout the case’s lifecycle.

This improves legal practice and improves the law itself by removing inefficiencies.

The Horizon Bias Problem

Horizon bias - focusing on the immediate next step without systematically considering second- and third-order consequences — is one of litigation’s most persistent costly failures. This is not intelligence failure but structural consequence: lawyers operate under time pressure with billing structures rewarding current task activity and institutional cultures prioritising next deadlines. Partners preparing summary judgment motions rarely rigorously model what happens if the motion fails; discovery obligations triggered, settlement dynamics shifted, appellate options opened or closed.

Lawgame’s multi-orbit architecture forces confrontation with the full game tree. When pursuing a primary Orbit 1 objective that fails, the system does not simply report failure. It analyses judicial feedback, identifies alternative pathways, and plays them in Orbit 2, automatically modelling what human teams often neglect: the strategic landscape beyond the immediate horizon.

Case 1.2 illustrates this precisely. A traditional team focused on immediate objectives would invest resources in winning the preliminary injunction motion. If it failed - as Lawgame’s simulation showed - the team would regroup, eventually identifying alternative approaches over weeks or months. Lawgame’s Orbit 2, triggered automatically by Orbit 1 failure, identified the Rule 26(d) expedited discovery path within minutes, having already thought one horizon ahead by architectural requirement.

This capability’s value increases with stakes and complexity. In simple single-issue disputes, horizon bias presents minor risk. In multi-front litigation involving regulatory enforcement, parallel civil and criminal proceedings, cross-border jurisdictional questions, or precedential appellate strategy, failure to think beyond the immediate move locks parties into paths foreclosing superior alternatives. Lawgame’s architecture prevents precisely this failure.

Target Market

Lawgame’s primary audience comprises three categories: law firms, corporate legal departments, and litigation funders. Each gains from different system capabilities.

Time compression. Strategy development normally requiring weeks or months of partner deliberation and iterative refinement is compressed to minutes or hours. For firms facing urgent deadlines - hearings in days, opposition briefs due next week - running a full adversarial simulation and identifying dominant strategy in under fifteen minutes transforms what is possible within the available window.

Cost avoidance. Lawgame performs the same function as human war-gaming at a fraction of the cost, with broader strategic coverage — exploring dozens of scenarios in the time and budget it takes a traditional team to explore one or two.

Pre-litigation intelligence. Clients can test case theory viability against adversarial opposition and judicial scrutiny before committing to expensive litigation. If the system identifies a dominant strategy, the case proceeds with confidence. If it cannot find a viable path, the client avoids the expense and reputational exposure of pursuing a losing position. This rigorous pre-commitment evaluation becomes routine when simulation is cheap and fast.

Litigation funding due diligence. Funders currently make investment decisions on static, one-directional case assessments. Lawgame enables simulation-based evaluation: observe how the case performs under adversarial pressure across multiple rounds, and make funding decisions informed not merely by legal strength but by strategic dynamics. The system’s capacity to identify dominant strategies, flag unwinnable positions, and surface Innovation Lab insights provides a qualitative advantage no existing tool offers.

1.8 Commercial Model & Roadmap Summary

The Commercial Case

A single simulation covers multiple orbits and dozens of rounds, testing a range of strategic approaches. The system can be re-run with modified inputs - different evidence, legal objectives, jurisdictional assumptions — at negligible marginal cost, transforming what was a discrete, expensive event into a continuous, iterative process.

Beyond simulation cost, the system reduces downstream litigation expenditure by identifying dominant strategies early or confirming no viable strategy exists. Case 2.1 illustrates this: value lay in confirming quickly and cheaply that no winning argument was available, sparing the client protracted unwinnable proceedings.

The Dual-Track Strategy

Lawgame’s development proceeds along two mutually reinforcing tracks.

Track 1: Commercial. Premium pricing for law firms, corporate legal departments, and litigation funders funds platform development, sustains engineering and research teams, and generates simulation data feeding the fine-tuning pipeline.

Track 2: Access to justice. Specialised versions serve independent practitioners competing with larger rivals, legal aid organisations serving under-resourced clients, and self-represented litigants navigating the legal system without strategic guidance.

The tracks are symbiotic, and the connection between them is direct: commercial revenue from premium-priced institutional licensing is the funding mechanism for access-to-justice development. Without Track 1 revenue, Track 2 cannot be built, maintained, or scaled. Without Track 2 deployment, the system fails its foundational purpose.

Access-to-justice deployment simultaneously generates simulation data across wider case types and jurisdictions than the institutional market alone would produce, improving system capabilities for all users, and making up a large part of the novel dataset that Lawgame will develop for our own downstream models. The commercial track funds the mission; the mission track strengthens the product. Neither is subordinate to the other; both are architecturally required.

The Access to Justice Imperative

The preceding sections describe Lawgame’s advantages relative to well-resourced traditional teams. The most significant comparison, however, is between Lawgame and no counsel, or between Lawgame-assisted representation and strategic thinking available to parties unable to afford KC-level advice.

Current reality is starkly stratified. Only clients with budgets measured in tens of millions access this calibre of strategic thinking.

For independent practitioners and small firms, a tailored version enables solo practitioners to access strategic tools reserved for large firms. Firms defending regulatory enforcement or pursuing commercial claims could run the same simulations as Magic Circle or AmLaw 100 firms at a fraction of the cost.

For legal aid and pro bono work, partnerships with legal aid organisations and public defender offices could bring elite-level strategic analysis to clients receiving none currently. In criminal defence, regulatory enforcement, housing, and employment disputes - where resource asymmetry between parties is most extreme - impact could be transformative.

For pro se litigants, a growing court population with substantially worse outcomes than represented parties could benefit from adapted Lawgame versions serving dual functions: improving legitimate claims’ strategic quality and providing honest pre-litigation assessment dissuading prospective litigants from pursuing likely-failing cases. This latter function — reducing frivolous pro se litigation through candid evaluation — benefits litigants, courts, and court systems bearing meritless filings’ administrative burdens.

The caveat is plain: exclusive premium-rate licensing to elite firms reproduces and potentially deepens existing legal services stratification. It strengthens the well-resourced without benefiting the under-resourced, representing core project failure. The democratisation agenda is not afterthought or marketing position, it is part of why Lawgame was built. If a system so powerful and transformative serves only the already-powerful, it has failed on its own terms.

1.9 Document Purpose, Audience & Reading Paths

This is a technical and conceptual whitepaper. It demonstrates four things.

First, how Lawgame works, its adversarial agent architecture, multi-orbit recursion mechanics, Innovation Lab synthesis engine, and model-agnostic deployment.

Second, what Lawgame proved across nine real litigation scenarios spanning commercial disputes, regulatory enforcement, and appellate strategy, including successes and very useful failures.

Third, what makes its outputs novel, not merely faster retrieval or more accurate prediction, but generation of strategic arguments exploiting doctrinal contradictions, cross-domain synthesis, and ontological reframing.

Fourth, why this represents a structural shift in litigation strategy and, if appropriately priced and distributed, advances access to justice.

The tone is measured and evidence-based. Every claim grounds in specific case outcomes. Shortcomings are stated plainly. The goal is demonstrating genuine innovation through evidence, not persuading through hyperbole.

Audience Entry Points

The document is written for several audiences at once. Rather than force all readers through every section, the following guide offers entry points by interest:

Venture capital and business decision-makers should begin with this section (positioning and summary), then turn to whichever case study in Section 4 is closest to their domain of interest.

Law firms and corporate legal departments will find most immediate value in Section 2.5 (deployment and security) and Section 7 , followed by the Section 4 cases relevant to their practice areas.

Legal academics and researchers should focus on Section 2 (architecture), Section 6 (emergent capabilities), and Section 10.4 (research agenda).

Technical implementers are directed to Section 2 , Section 8 , and the Technical Appendices in Section 10.5 .

Legal technology companies will want Section 1.6 in this page (competitive positioning) and Section 7 (strategic positioning and roadmap).

1.10 About the Author - Luke Cohen

In 2018, when the AI world’s most capable tools were narrow classifiers and the idea of a reasoning model was still science fiction, Luke built the world’s first legal image model at LegalZoom. It used computer vision to identify and classify legal documents with nothing more than a phone camera — a system that only made sense if you believed law was fundamentally a structured information problem, not a human intuition one. Almost nobody believed that yet. Building it required thinking about legal knowledge the way an engineer thinks about data, years before that became the industry’s default assumption.

Cohen is the CEO of Citational . His career has moved consistently toward the same question from different angles: what does it actually take to get AI to reason about law correctly, not just fluently? That question has taken him through Tier 1 law firm consultancy in London and New York. Earlier, he carried out strategic advisory work for WPP, IBM, and Deloitte, a technology policy role at the United Nations (2003–05), and technical advisory work for the UK Foreign & Commonwealth Office. He has direct experience in contentious civil litigation — where the gap between algorithmic confidence and judicial reality is most expensive.

His grounding spans computer science and legal systems in equal depth; he writes C and PHP for the love of it, and recently created a native GPT with no imports in 116 lines of C , (inspired by Andrej Karpathy’s 224-line Python implementation). That combination of engineering instinct and legal systems thinking is what meaningful legal tech innovation requires, and what makes Lawgame possible.

Contact: luke.cohen@citation.al

Connect on X: @CuriousLuke93x