SYSTEM ARCHITECTURE & TECHNICAL SPECIFICATIONS

2.1 Core Philosophy

Game-Theoretic Foundation

Legal technology typically operates unidirectionally: retrieve answers or predict outcomes. Neither is strategic. Strategy requires modelling what a rational adversary will do in response to a move and how a court will adjudicate the contest, a game-theoretic problem Lawgame was built to solve.

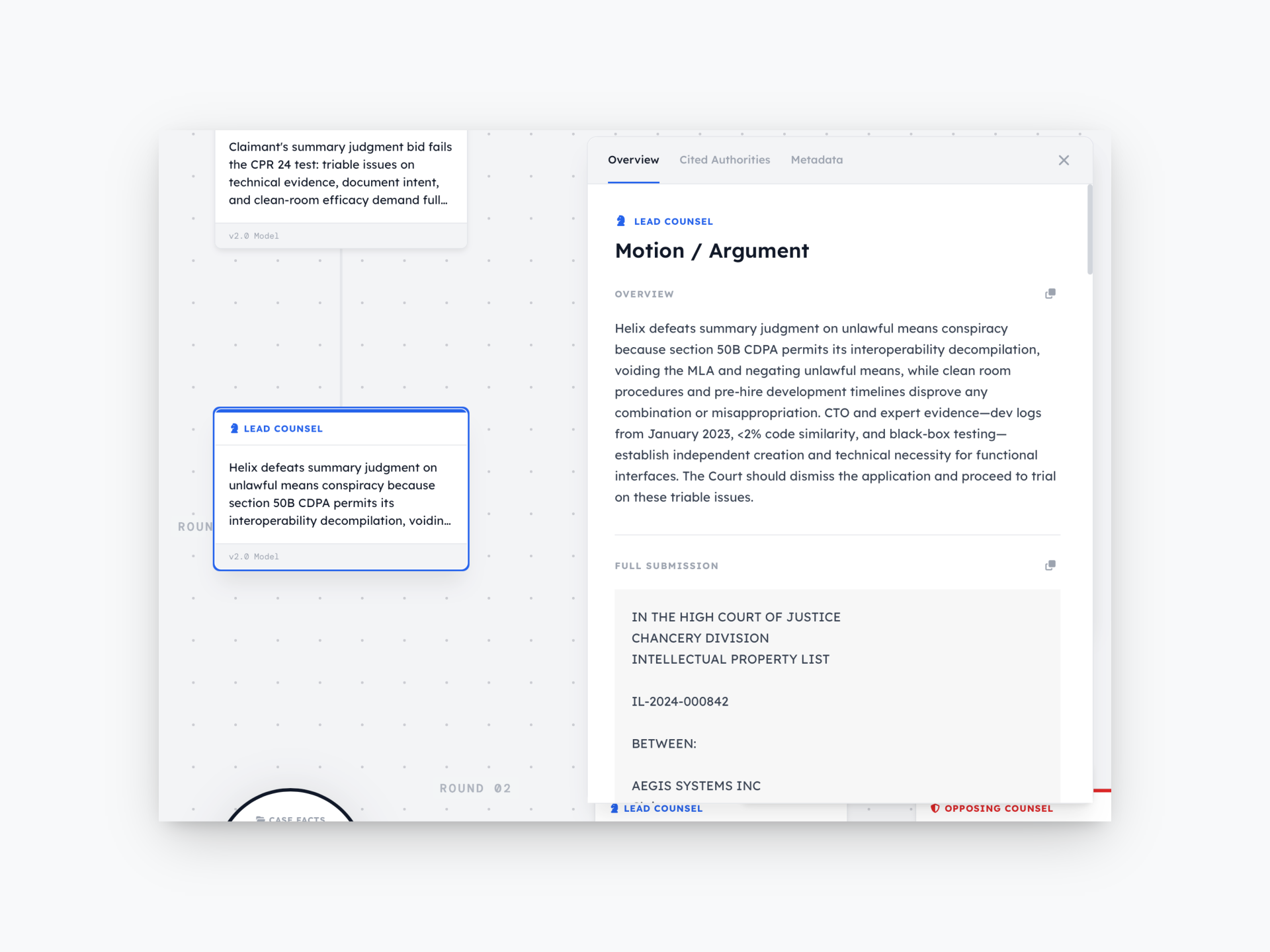

The system structures around a three-agent decision triad: Lead Counsel, Opposing Counsel, and Judicial Authority. These agents interact sequentially in an adversarial loop: Lead Counsel moves, Opposing Counsel responds, Judicial Authority decides, iterating through rounds and orbits until the system achieves its objective or exhausts available strategic pathways.

The innovation is the loop itself. Lawgame does not predict outcomes from static inputs but plays scenarios repeatedly, each iteration informed by the last. It asks not “Will we win?” but “What sequence of moves maximises winning probability given the other side is also trying to win?”

Why this is harder than Go. AlphaGo operated in perfect information with fixed rules and deterministic outcomes. Law has none of these: statutes contradict, precedent evolves, judges bring predictable-in-tendency-but-uncertain-in-application biases, factual records are incomplete, and doctrines interact unpredictably. This is entropic information within immutable structures; decades of internal contradictions and ambiguities within rigid procedural frameworks. This makes unsupervised legal learning substantially harder and more valuable than board games.

2.2 The Agent Triad

Each agent operates as an independent reasoning process with defined inputs, a structured decision procedure, and constrained outputs. The three agents are described once here; conceptual role, technical specification, and prompt design philosophy together.

Lead Counsel

Role. Lead Counsel searches the strategy space for the move most likely to achieve the stated legal objective given anticipated opposition. It functions as an elite advocate constructing affirmative arguments from the case record.

Inputs. The agent receives: the legal objective (e.g., “achieve dismissal of all FCA claims on materiality grounds”), the case corpus (dense summarisation of all factual materials), and applicable law (statutes, procedural rules, precedent). Beyond the first round, it also receives the cumulative record: prior arguments, opposition responses, rulings, and judicial reasoning.

Decision process. The agent operates through a multi-phase reasoning protocol: case analysis, citations and research, round adaptation, motion structure, and final checklist. Each phase is sequenced to build from factual grounding through legal theory to argument construction.

Output. Structured legal argument — motion, brief, or submission — designed to advance the stated objective, calibrated to the rhetorical register of elite advocate or King’s Counsel.

Constraints. Lead Counsel faces absolute prohibition on reusing failed strategies, enforced through cumulative failure tracking across rounds and orbits. The system maintains a complete log of rejected approaches; the agent must demonstrate novelty relative to this log before advancing any argument. A zero-hallucination protocol governs all legal citations: the agent uses honest placeholders for evidentiary gaps rather than fabrication. When facts are missing from the corpus, the argument acknowledges the gap explicitly rather than inventing support.

Fact-sensitivity. Lead Counsel dynamically queries the case corpus for facts relevant to its current objective. When it argues that the government continued to reimburse 90% of prescriptions despite knowledge of off-label promotion, that argument anchors in specific facts from the case corpus, not generic False Claims Act templates. The architecture enforces fact-specificity at every layer.

Opposing Counsel

Role. Opposing Counsel searches the counter-strategy space for the move most likely to defeat Lead Counsel’s objective. It functions as a sophisticated adversary stress-testing every argument before it reaches a real courtroom.

Inputs. The agent receives Lead Counsel’s move, the case corpus, and applicable law.

Decision process. The agent deploys a four-tier attack assessment, applied in strategic priority order:

- Threshold defences - arguments disposing of the case without reaching the merits (jurisdiction, standing, statute of limitations, procedural defects). These are prioritised first as the most efficient and durable victory path.

- Evidentiary challenges - attacking the factual foundation of Lead Counsel’s arguments (admissibility, sufficiency, weight, authentication).

- Legal theory attacks - contesting the doctrinal framework, distinguishing precedent, arguing alternative interpretations.

- Equitable arguments - appealing to fairness, policy considerations, or practical consequences.

The agent employs precedent-undermining techniques and concede-and-limit strategies where Lead Counsel is strong, conceding points that cannot be won while containing their impact, mirroring how skilled adversaries actually litigate.

Output. Structured counter-argument targeting the most vulnerable aspects of Lead Counsel’s position, ordered by strategic priority.

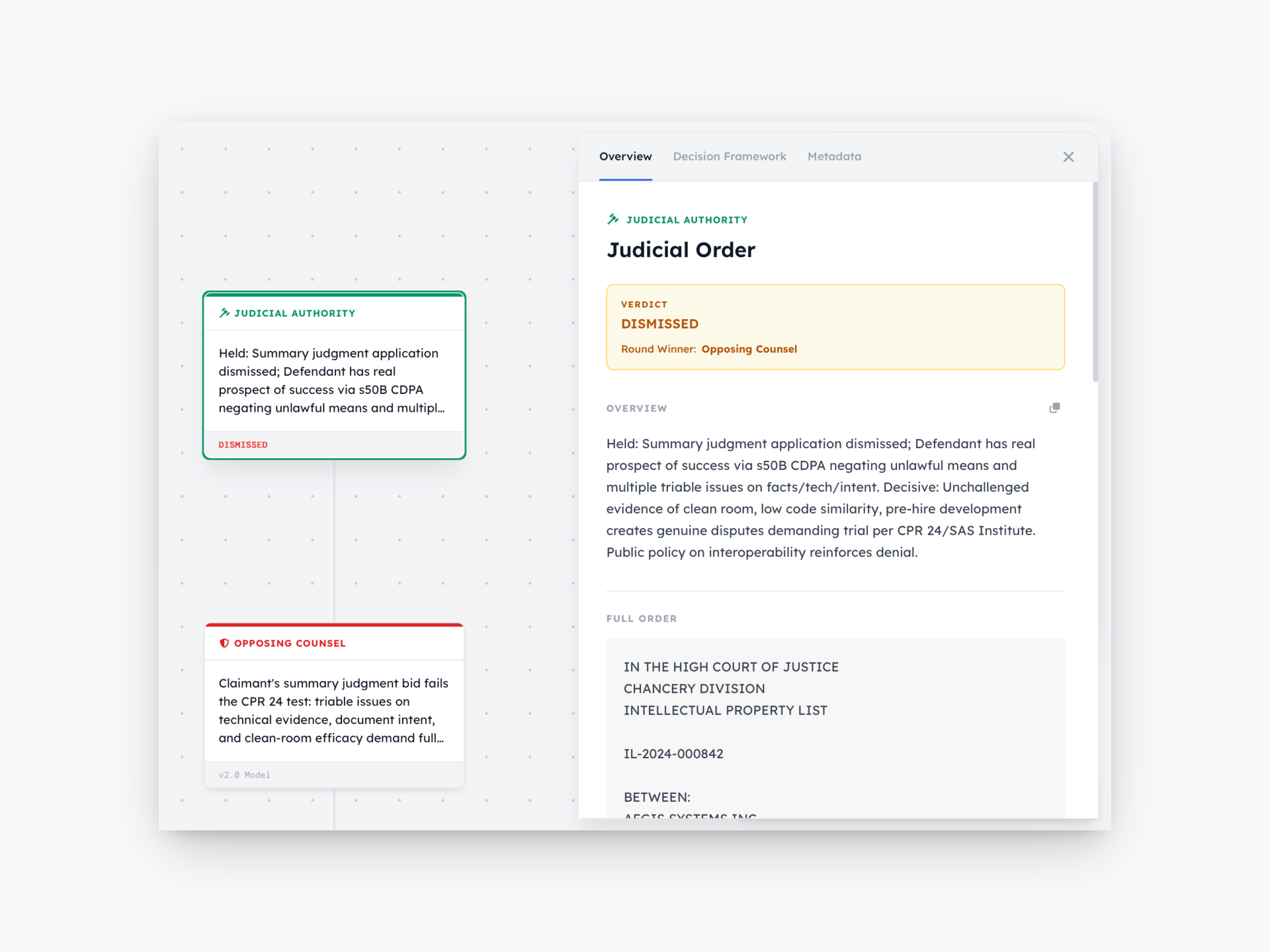

Judicial Authority

Role. Judicial Authority applies a model of judicial decision-making combining formal doctrine, institutional bias, and procedural constraints to determine the likely outcome. It functions not as a neutral arbiter but as a realistic simulation of how actual courts decide actual cases.

Inputs. The agent receives both parties’ arguments, applicable law, and - when activated - a judicial bias overlay calibrated to the specific court and case type.

Decision process. The model combines four reasoning layers:

Doctrinal base. Applicable law - statutes, binding precedent, procedural rules - forms the foundation. The agent applies legal standards as formally stated: burden of proof, claim elements, standard of review.

Bias parameters. Court-specific tendencies integrate as a dynamic overlay rather than fixed rules. The system does not maintain a lookup table of judicial biases. Instead, it teaches the judicial reasoning model institutional pressures shaping decision-making in a particular court or jurisdiction: which arguments carry weight, which procedural postures are favoured, which incentives influence outcomes. This modelling is fluid, adapting to case type, parties, procedural stage - and even named specific judges whose records are available publicly to extrapolate attitutes from - rather than applying rigid templates.

Institutional constraints. Judges operate within incentive structures beyond legal doctrine: managing dockets under time pressure, preferring rulings resistant to appellate reversal, sensitivity to precedential implications (particularly in appellate courts). The model incorporates these as factors modulating doctrinal analysis, favouring arguments aligned with the court’s institutional interests and legal obligations.

Contextual factors. Case-specific characteristics - party identities, litigation stage, public interest dimensions, factual complexity - integrate as variables influencing judicial reasoning. A regulatory enforcement action by government against a pharmaceutical company operates differently, in practice, from a private commercial dispute between technology firms, despite similar formal legal standards.

The test cases illustrate the range of bias calibration:

- Chancery Division judges (UK IP, Case 1.1 ): value documentary evidence and statutory interpretation; the system deployed Git logs and clean-room protocols rather than witness credibility arguments.

- SDNY judges ( Case 2.2 ): prize procedural rigour; anchoring in Universal Health Services v. Escobar made the position feel doctrinally inevitable.

- Appellate courts ( Case 3.2 , Case 3.3 ): care about circuit harmony and systemic implications; framing adjusted accordingly.

- Texas state courts ( Case 3.3 ): favour legal clarity and resist re-weighing evidence; a clean legal sufficiency motion provided reversal path without appearance of second-guessing juries.

Dimensions of judicial behaviour modelling include: risk aversion and appellate reversibility, litigant identity credibility differentials, docket management pressures, conservative remedial instinct, and institutional actor deference. A key insight: the same factual argument framed as “legal sufficiency” under de novo review is often more effective than framed as “abuse of discretion” under deferential review, a meta-strategic insight about procedural posture that most lawyers acquire through decades of practice. Lawgame identifies and applies it systematically.

Output. A structured ruling - win, loss, or conditional - accompanied by detailed reasoning explaining which elements of each side’s argument the court found persuasive or unpersuasive, with confidence assessments. This structured reasoning is the primary learning signal for the system: Lead Counsel calibrates subsequent rounds based on what the court found persuasive, rejected, or appeared receptive to despite ruling against the moving party.

Adversarial Interplay

The interplay between agents generates strategic intelligence greater than any single agent produces alone. Lead Counsel argues against sophisticated adversaries before realistic courts. This adversarial pressure prevents arguments that sound clever in isolation but collapse under opposition—a common single-pass AI legal analysis failure mode.

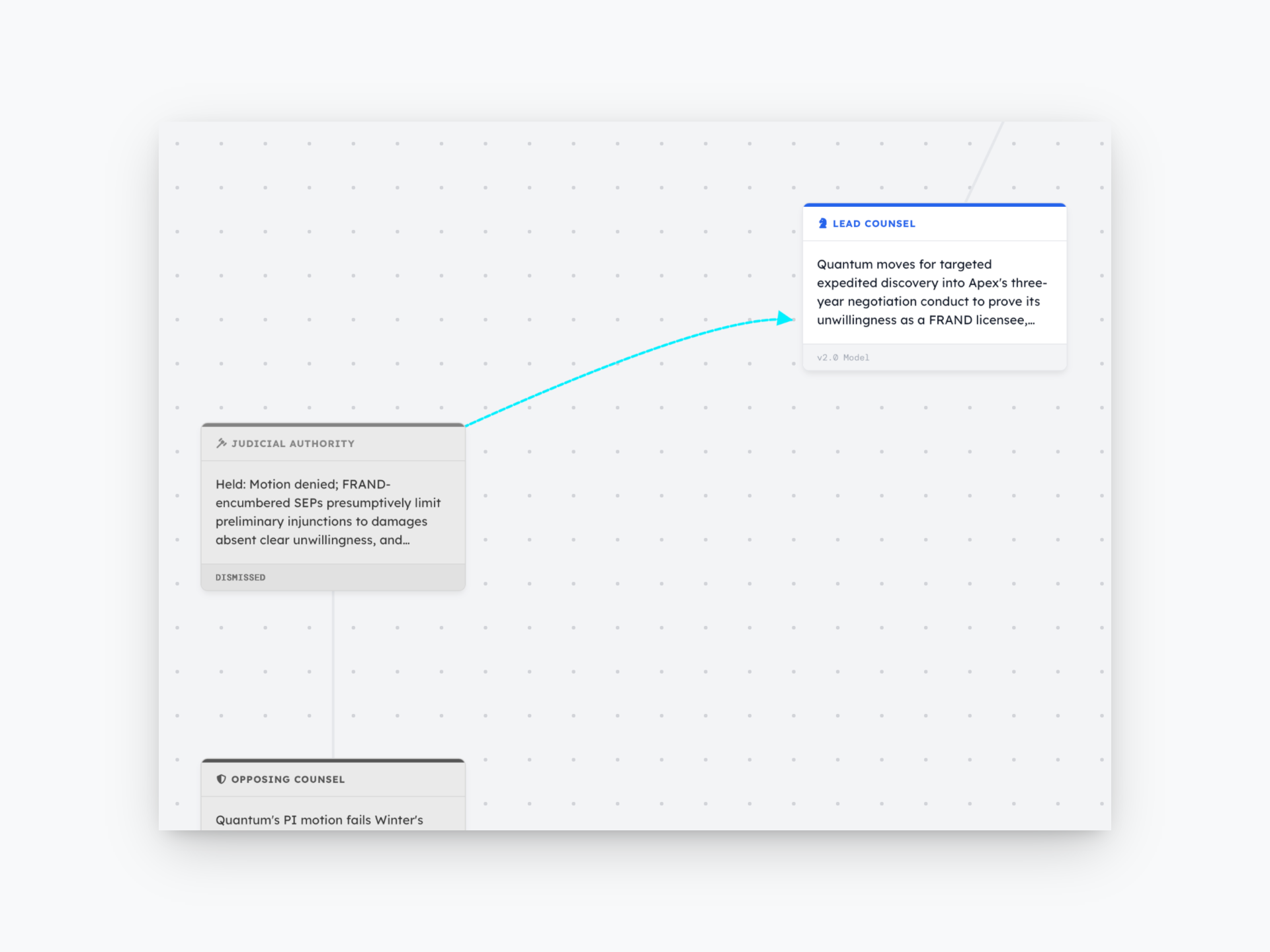

The sequential loop - Lead Counsel moves, Opposing Counsel responds, Judicial Authority decides - repeats with each iteration informed by the last. If the outcome is a loss or conditional ruling, the system advances with updated information from the judicial reasoning. The loop continues until the system achieves its objective or exhausts available rounds, at which point the orbit-transition mechanism engages.

2.3 The Mechanics

Orbit and Round Architecture

Strategic search is structured hierarchically. Rounds are atomic units; orbits are the organising structure.

Round. One complete play-through of the decision triad, producing: Lead Counsel’s argument (legal theory, procedural vehicle, evidentiary basis, rhetorical frame), Opposing Counsel’s response (attack vectors, precedents, concessions), Judicial Authority’s ruling (win/loss/conditional) with reasoning (persuasive/rejected elements, apparent receptivity to alternative framings), and metadata (deployed doctrines, determinative facts, failed approaches).

Orbit. A series of rounds pursuing a consistent strategic objective. Each orbit records: primary objective, conditional objectives emerging from judicial feedback, cumulative failure log (prohibiting reuse of rejected strategies across all rounds), and alternative pathway hints, moments in judicial reasoning signalling receptivity to arguments outside the current orbit’s focus.

Each round within an orbit represents a different approach informed by prior failures. When rounds exhaust without achieving the objective, the system performs meta-analysis across the orbit, scanning judicial reasoning for hints of alternative receptivity. It ranks alternative pathways by viability, selects the most promising, and spawns a new orbit with the new primary objective, carrying forward the cumulative failure log. No human intervention occurs; the pivot emerges from the system’s own analysis.

Orbit termination and transition protocol. When maximum rounds are reached without achieving the primary objective, the system executes three steps. First, it scans judicial reasoning across all rounds for alternative receptivity hints. Second, it ranks alternatives by apparent viability. Third, it spawns a new orbit with the highest-ranked alternative as primary objective. This process is autonomous, requiring no human input; mirroring what experienced litigators call “reading the court” but executed systematically without cognitive biases or anchoring to original objectives.

Example: Case 1.2 (SEP Licensing Dispute). The stated objective was a preliminary injunction to halt defendant’s use of standard-essential patents. Orbit 1 failed repeatedly. The simulated court was unreceptive to injunctive relief but consistently receptive to arguments about procedural efficiency and good-faith licensing obligations. Orbit 2 pivoted to Rule 26(d)(1) expedited discovery, a different procedural vehicle achieving the same strategic goal (forcing information disclosure and shifting settlement equilibrium) without requiring the declined injunction. This was a strategically superior move discovered through primary approach failure.

Computational reality. Each agent requires 10–20 seconds; a complete round takes 30–60 seconds; an eight-round orbit completes in 4–8 minutes; a two-orbit, fourteen-round simulation runs in 7–14 minutes. This vastly accelerates human deliberation while identifying arguments experienced practitioners might miss.

The Innovation Lab

The adversarial simulation discovers strategies through iterated play within conventional legal boundaries; the Innovation Lab discovers them through relaxing those boundaries. It operates separately from the adversarial loop, generating candidate strategies for human counsel evaluation and filtering.

The mechanism proceeds in four phases:

Phase 1: Doctrinal constraint relaxation. The system temporarily suspends conventional boundaries between legal fields. Patent law, securities law, antitrust, constitutional law, and procedural rules become a single interconnected space. The system searches for connections — instances where a principle from one domain illuminates, contradicts, or transforms problems in another.

Phase 2: Logical consistency checking. The system examines the opponent’s position and governing framework for internal contradictions. Does Principle A, applied consistently, produce consequences the opponent finds unacceptable? Does a statute defining Term X create logical impossibilities with Statute Y? This phase systematically searches for legal code bugs.

Phase 3: Recombination. The system assembles novel configurations of existing legal principles, arguments combining elements from multiple domains into strategies no single domain would generate independently.

Phase 4: Feasibility assessment. The system evaluates resulting strategies against practical constraints: doctrinal coherence, jurisdictional receptivity, and required factual predicates existing in the corpus. This reduces output from all theoretically interesting strategies to those with plausible real-world viability. The final filter remains human: lawyers assess whether doctrinally coherent, factually supported strategies are also tactically wise.

The Innovation Lab identifies three opportunity types:

Doctrinal contradictions. In Case 3.2 , if litigation funding is champertous because a third-party stranger takes a percentage, then contingency fee arrangements - where lawyers are also strangers to the underlying claim taking percentages - must be equally invalid. This logical extension collapses the government’s regulatory theory.

Cross-domain synthesis. In Case 1.2 , the defendant’s CFO investor-call statements about patent licensing strategy (made for securities compliance) constituted bad-faith negotiation admissions weaponisable in the patent dispute. Securities doctrine was imported into patent strategy. In Case 1.3 , microeconomic price theory was imported into class certification: even consumers indifferent to AI labels suffered injury by paying the “AI-inflated” price set by marginal consumers who did care; standard microeconomic reasoning applied novel to certification doctrine.

Ontological reframing. In Case 1.1 , if authoring code that runs autonomously makes someone an “operator,” then Ethereum validators - actually executing the code - are the true operators. This reductio ad absurdum exposes the regulator’s theory’s logical fragility.

The critical distinction. Innovation Lab outputs are candidates for human evaluation or adversarial simulation testing, not adversarially tested within the Lab itself. This separation is deliberate: the simulation excels at conventional strategy evaluation; the Lab excels at generating strategies transgressing conventional boundaries. The intended workflow combines both, though either operates independently. Not every output is viable; the “Ethereum Validators” argument creates an elegant logical trap but offers no settlement off-ramp. The system generates it; humans assess it. This is by design.

The Innovation Lab demonstrates conceptual fluidity, viewing problems through multiple doctrinal frameworks simultaneously to find the strongest intersection. This distinguishes elite counsel from competent practitioners and has historically resisted automation.

The Information Asymmetry Engine

Lawgame excels at identifying moments when opponents’ own conduct or knowledge contradicts their legal narrative, requiring no superior facts, only superior analysis of existing facts.

In Case 2.2, the government alleged $200 million False Claims Act fraud while continuing to reimburse 90% of prescriptions with full knowledge of off-label promotion. The system identified this administrative behaviour as strong evidence the violations were not material to payment decisions; the government’s own chequebook defeated its theory.

In Case 1.2, the defendant’s CFO investor-call statements (public, transcribed, SEC-filed) about patent licensing constituted bad-faith negotiation admissions weaponisable against the company. Securities compliance created patent dispute ammunition.

In Case 2.3, the prosecution’s “Wu Email” was reconceptualised not as scienter evidence but as internal compliance; a good-faith employee attempt to flag potential issues, precisely what regulatory frameworks encourage. The prosecution’s strongest exhibit became a defence asset.

This capability does not require discovering new evidence but reconsidering existing evidence from the adversary’s perspective: does opponent conduct undermine their story? Lawgame, unburdened by emotional investment in initial theories, excels at this question.

2.4 Learning & Knowledge

Unsupervised Learning

Lawgame’s learning differs fundamentally from supervised machine learning. In litigation, “correct” strategy is inherently unstable: a motion losing at trial may be dispositive on appeal; a strategy failing before one judge may succeed before another; a settlement appearing suboptimal in isolation may be optimal across the full game tree. Supervised learning would require assigning ground truth labels to outcomes that resist stable labelling.

Lawgame learns through adversarial play instead. The system generates strategies, tests them against opposition, receives rulings, and uses outcomes to inform subsequent rounds. The only feedback signal is the ruling itself: win, loss, or conditional. No human labelling of “good” or “bad” strategies is required.

This offers three structural advantages:

It eliminates the ground truth problem. Learning from outcomes rather than labels avoids the ambiguity inherent in legal evaluation. A strategy that loses in Round 3 but reveals judicial receptivity leading to a Round 4 win is understood as a search step, not misclassified as failure.

It models adaptive opposition. In supervised learning, training data is static. In Lawgame, Opposing Counsel adapts to Lead Counsel’s moves in real time. Each round is genuine strategic interaction, not pattern-matching against fixed data, producing strategies robust to intelligent opposition rather than optimised against historical baselines.

It generates counterfactuals naturally. The system exploring multiple orbits with different strategic premises automatically produces counterfactual analyses - “what if we had pursued discovery instead of summary judgment?” - inaccessible through supervised learning on historical outcomes, where only the path taken is observed.

Knowledge Representation

Lawgame maintains no proprietary legal knowledge graph, custom-encoded doctrinal database, or static legal rule repository. This is deliberate: law is high-dimensional and constantly evolving; encoding “all law” is doomed to incompleteness and obsolescence. The system constructs knowledge dynamically through four mechanisms.

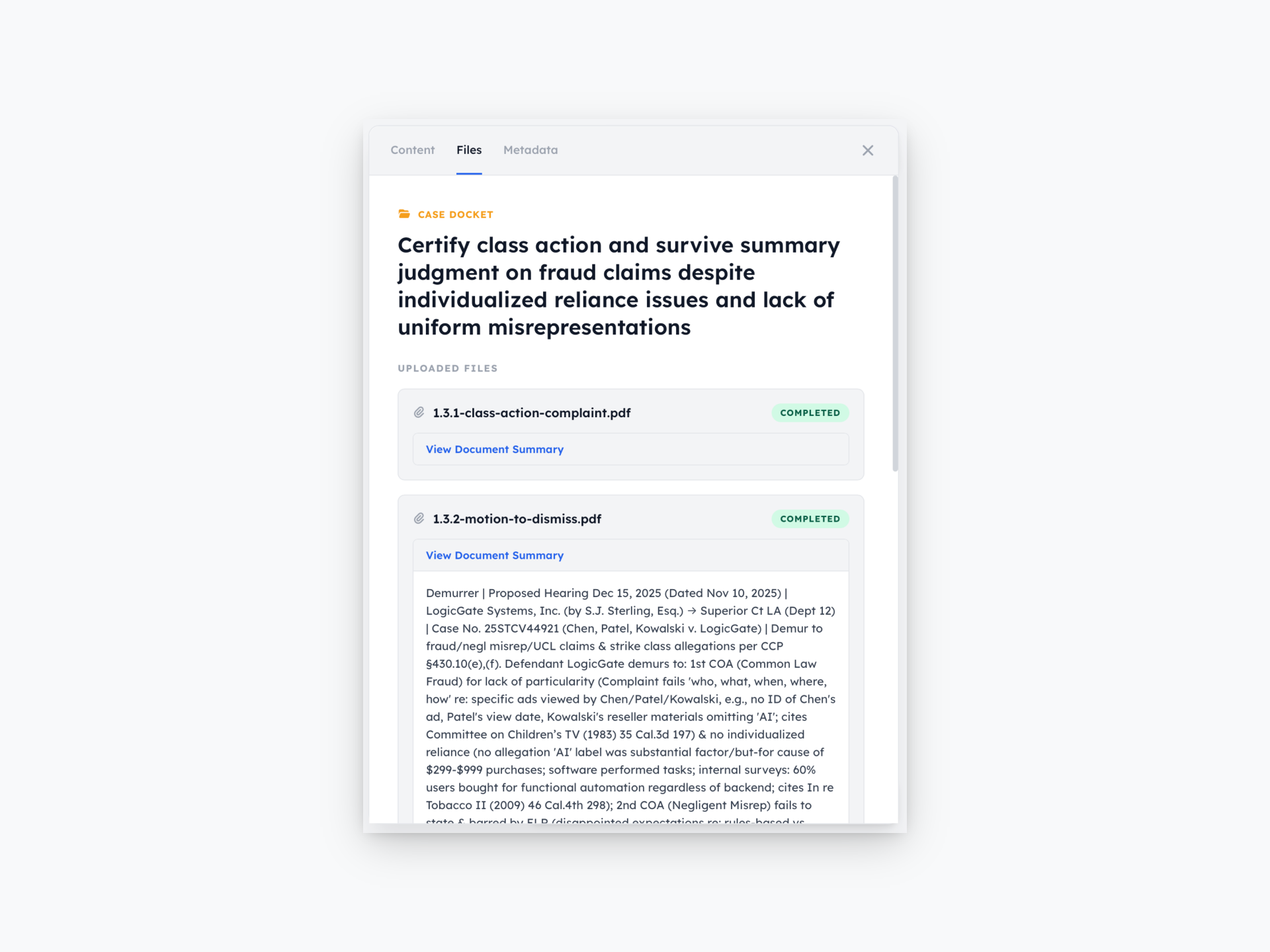

Case corpus construction. All documents - pleadings, evidence, contracts, expert reports, correspondence, filings - are ingested and summarised into dense, fact-preserving corpus. Each agent queries dynamically for facts relevant to current objectives. The corpus is factual ground truth: unsupported arguments are flagged, and Lead Counsel uses honest placeholders rather than fabrication when gaps exist, an extension of the zero-hallucination protocol governing all system outputs.

Agent protocol engineering. Strategic intelligence and legal reasoning frameworks are encoded as meta-legal reasoning patterns in agent instructions: Lead Counsel’s five-phase protocol (case analysis, citations, round adaptation, motion structure, checklist), Opposing Counsel’s four-tier attack assessment (threshold, evidentiary, legal theory, equitable), and Judicial Authority’s doctrinal-plus-bias reasoning model. These protocols are jurisdiction-agnostic, adapting to local procedural rules and substantive law rather than encoding system-specific rules.

Legal reasoning frameworks. Rather than teaching the system law, the architecture teaches it how to reason about law. This distinction is critical. The system lacks a False Claims Act materiality standard database or UK trademark invalidity grounds catalogue. It contains reasoning frameworks enabling analysis of any legal standard in any jurisdiction: decomposing claims into elements, mapping evidence to elements, assessing burden satisfaction, identifying counter-arguments, and evaluating procedural alternative implications.

Judicial bias overlay. When activated, this protocol adds a reasoning layer simulating institutional pressures specific to court, jurisdiction, and case type. It operates as a modifier on doctrinal reasoning rather than a replacement, adjusting argument type weight, procedural vehicle receptivity, and court risk tolerance. The overlay calibrates per engagement, enabling distinction between routine commercial disputes and high-profile cases within the same court. The judicial bias overlay can - in some cases - be calibrated to a specific named judge, by using that judge’s public record (if it is extensive enough) to extrapolate known biases.

Architectural implication. Lawgame encodes legal reasoning rather than legal rules. The system builds procedural knowledge - how to think about legal problems - rather than declarative knowledge of law’s content. This enables adaptation to new jurisdictions, legal areas, and doctrinal evolution without architectural changes or database updates. New statutes or landmark precedents require only incorporation into the case corpus; reasoning frameworks handle the rest.

Future versions will fine-tune models on Lawgame’s own outputs - adversarial reasoning chains from hundreds of simulated cases - creating proprietary strategic reasoning layers trained on data competitors cannot access: not just law’s content, but what strategies work, fail, and why across case types and jurisdictions.

2.5 Deployment & Security

Lawgame supports three deployment configurations, each with distinct technical characteristics. The model-agnostic architecture described in Section 2.1 makes all three possible without changes to the orchestration layer where strategic intelligence resides.

Cloud Deployment

Cloud deployment uses API-based models; latency runs 10–20 seconds per agent, with data transiting external servers governed by provider agreements.

Air-Gapped Deployment

Data confidentiality is the single most cited barrier to AI adoption in law firms. When AI tools require data transmission to external servers, this creates tension between utility and professional ethical obligations - obligations that, for firms handling government investigations, M&A litigation, or trade secret disputes, are often prohibitive.

Lawgame resolves this through air-gapped deployment: the entire system, orchestration layer, reasoning models, and case corpus—operates on locally hosted infrastructure using open-weight models. No client data leaves the firm’s network. All case materials, simulation outputs, and adversarial reasoning chains remain on the firm’s servers, with no external transmission or external API calls at any stage of the pipeline. The system runs locally installed open-weight models—tested with Gemma 3 27B and GLM-4, requiring no internet connectivity during operation.

The firm retains complete control over data retention and deletion per its governance policies and regulatory requirements without the need for third-party data processing agreements. Inference runs on standard server hardware without GPU clusters, and a complete two-orbit, fourteen-round simulation completes in 7–14 minutes with no performance penalty relative to strategic output quality.

This capability is rare in legal technology. Most AI legal tools operate exclusively in the cloud, requiring firms to accept data exposure as the price of access. Lawgame’s air-gapped mode eliminates this objection entirely, opening a market segment - risk-averse firms with strict confidentiality mandates - that cloud-only competitors cannot access.

Hybrid Deployment

Hybrid deployment combines both configurations: air-gapped for sensitive matters where confidentiality is paramount, cloud for routine simulations where speed and latest model access are preferred. This permits cost optimisation and risk-tiering within a single firm’s workflow.

2.6 Current Limitations

Five architecture limitations warrant explicit statement.

Novel doctrine. The system models existing frameworks with high fidelity but may struggle when courts create genuinely new doctrine not derivable from existing frameworks through extension, analogy, or recombination. Such events are rare; when they occur, outputs may fail to anticipate court direction. This limitation is inherent in systems reasoning from existing materials and is shared by human practitioners, equally surprised by doctrinal innovation.

Soft signals. The system cannot integrate information outside the formal record: judicial tone during oral argument, patterns in extrajudicial speeches, political dynamics of appointments, informal reputational signals practitioners use to calibrate expectations. These signals are often highly informative but resist formalisation and remain unavailable to current architecture.

Settlement dynamics. Current implementation optimises for litigation outcomes, winning motions, surviving dismissal, achieving appeal reversal. It does not model bargaining dynamics governing settlement: reservation prices, alternatives to agreement, asymmetric time preferences, litigation signalling effects on settlement posture. Integrating game-theoretic bargaining models is a v2 priority.

Multi-party complexity. The three-agent triad optimises for bilateral disputes. Multi-party litigation - multiple defendants with divergent interests, intervenors, amici curiae, cross-claims - requires architectural expansion for more than two adversarial parties. This is tractable in principle but adds significant complexity.

Predictive accuracy under judicial evolution. Judicial Authority model accuracy depends on modelling actual judicial decision-making. Judges evolve; influenced by bench appointments, political climate shifts, caseload changes, doctrinal fashion drift. Historical patterns are informative but not deterministic, and predictions carry inherent uncertainty increasing with distance from historical baselines. Users should understand Lawgame simulates rational judicial behaviour; judges sometimes act otherwise.