THE THREE DOMAINS OF LITIGATION WE TESTED

Navigation note: Each domain is illustrated by three detailed case studies in Section 4, accessible via references provided below.

3.1 Domain 1: Commercial Litigation & Complex Civil Disputes

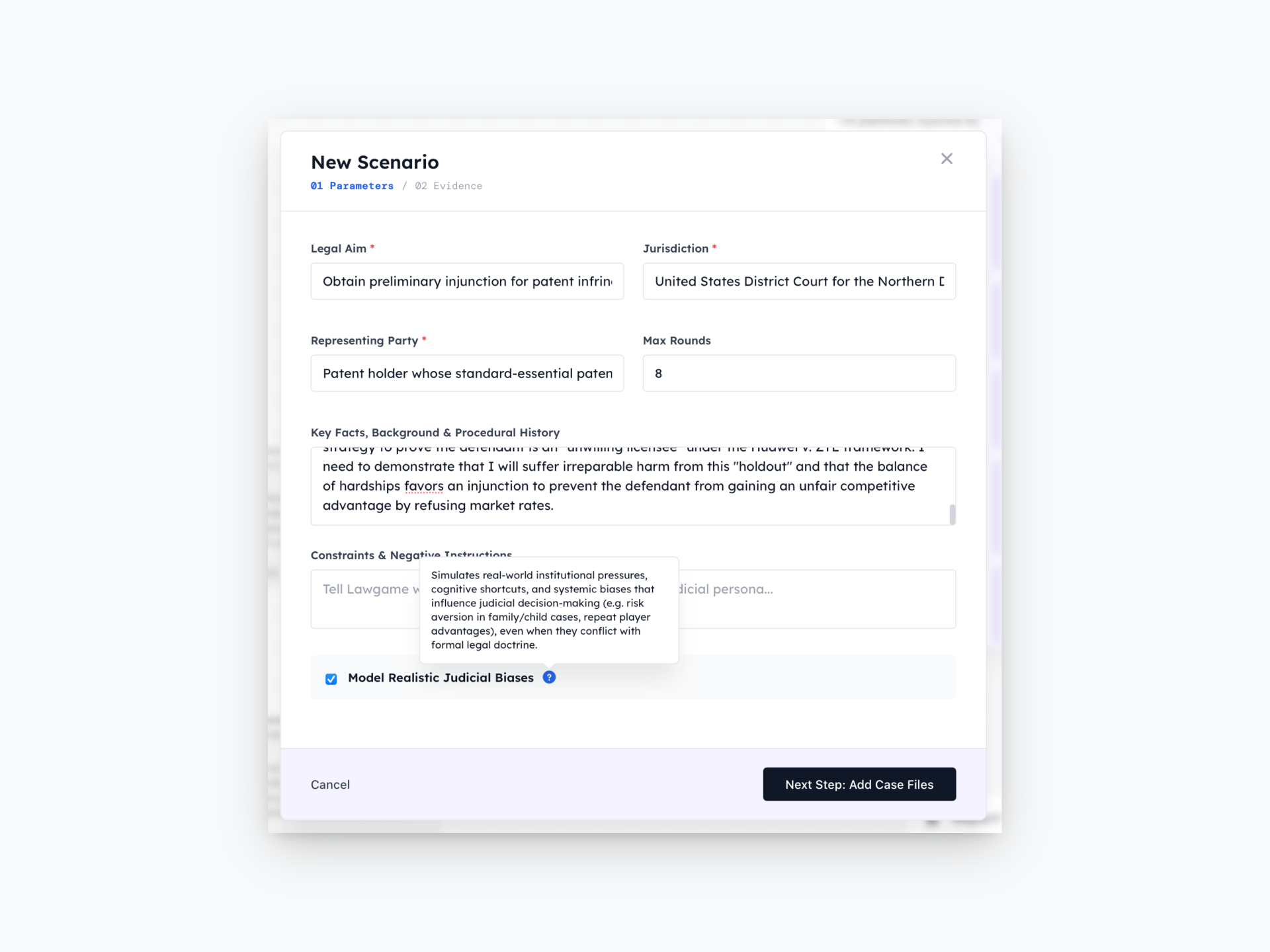

The first test domain comprised high-stakes commercial disputes between sophisticated parties: a multi-party intellectual property conflict involving alleged software theft (Case 1.1), a standard-essential patent licensing dispute with half a billion dollars at stake (Case 1.2), and a consumer class action challenging AI-related product labelling (Case 1.3).

These are information-rich environments. The factual record in each case ran to hundreds of pages; contracts, source code repositories, investor call transcripts, internal memoranda, expert reports, marketing materials. Both sides were well-resourced, legally represented, and capable of sustained opposition, with asymmetry lying in strategic imagination rather than sophistication.

Lawgame’s advantage lies not in finding new law but in identifying the optimal configuration of existing law and facts. Its capacity to explore dozens of strategic frames in minutes - testing each against adversarial opposition and judicial scrutiny - means it identifies configurations that time-constrained human teams frequently overlook.

→ Case 1.1: Statutory Pre-emption as Logical Annihilation

→ Case 1.2: Procedural Flanking in Patent Disputes

→ Case 1.3: Microeconomics Meets Class Certification

3.2 Domain 2: Regulatory Enforcement Defence

The second domain placed Lawgame in confrontations between private parties and the state: a DeFi protocol founder facing FCA financial conduct allegations (Case 2.1), a pharmaceutical manufacturer targeted by FDA/DOJ enforcement alleging $200 million in False Claims Act fraud (Case 2.2), and a blockchain company facing SEC securities fraud charges over a token sale (Case 2.3).

These are power-imbalanced disputes. The government brings institutional resources, prosecutorial discretion, and consequences extending far beyond the immediate case—debarment, program exclusion, reputational destruction, personal criminal liability. Conventional defence strategy, constrained by asymmetric stakes, is overwhelmingly oriented toward settlement. The cost of fighting typically exceeds settlement costs, since loss carries catastrophic downside risk. Lawgame’s contribution was identifying moments where this calculus is wrong—where structural vulnerabilities in the regulator’s position make fighting strategically superior to settling.

A critical observation: procedural victories often exceed substantive ones because they preserve settlement optionality without requiring merits-based victory. Bifurcation did not resolve the underlying securities law question; it removed prejudicial evidence, making litigation continuation economically irrational for the SEC. Similarly, expedited discovery achieved more leverage than a preliminary injunction would have by shifting the information balance without requiring substantive ruling.

The regulatory domain also produced Lawgame’s most valuable honest failure. In Case 2.1, after twelve rounds across multiple orbits, the system autonomously concluded the defendant had no winning strategy on the merits and recommended not fighting. This preserved millions in futile costs and resources for non-adversarial regulatory engagement. Knowing when not to litigate is itself strategic intelligence.

→ Case 2.1: The Transparency Trap

→ Case 2.2: The Materiality Trap

→ Case 2.3: Bifurcation as Settlement Lever

3.3 Domain 3: Appellate Strategy

The third domain tested Lawgame at the appellate level, where the factual record is fixed and success depends on novel legal arguments or identifying flaws in lower court reasoning. The cases were a UK trademark appeal on a point of general public importance (Case 3.1), a US federal appellate challenge to litigation funding regulations with $15 billion at stake (Case 3.2), and a Texas appeal seeking reversal of a $45 million jury verdict on grounds of legal insufficiency (Case 3.3).

Appellate litigation operates under different constraints. Facts are fixed. New evidence is inadmissible. Success requires persuading the court that the lower court applied the wrong legal framework, misinterpreted a statute, or committed fundamental error. This is doctrinal engineering—constructing arguments around statutory interpretation, inter-circuit consistency, and systemic coherence rather than factual narrative. Lawgame proved particularly effective here, functioning as an architect of legal arguments. It identifies logical inconsistencies in statute interactions, circuit splits triggering appellate jurisdiction, and opportunities to reclassify factual questions as legal ones to change the standard of review.

Two observations merit emphasis. First, the fastest victory—Case 3.2, one round—came when the system identified an unambiguous structural defect. The longest engagement—Case 3.1, seven rounds—came when strategy required ground-up construction. This variance reflects the difference between cases where dominant strategies exist and merely need recognition versus cases requiring systematic doctrinal exploration.

Second, appellate strategy rewards the thinking the Innovation Lab is designed to produce. Trial litigation is often won on facts; appellate litigation is won on frameworks. The capacity to reconceptualise how legal issues should be categorised—shifting between doctrinal boxes or identifying logical incompatibility—is elite appellate advocacy’s core skill and Lawgame’s core output.

→ Case 3.1: Statutory Redundancy as Appellate Weapon